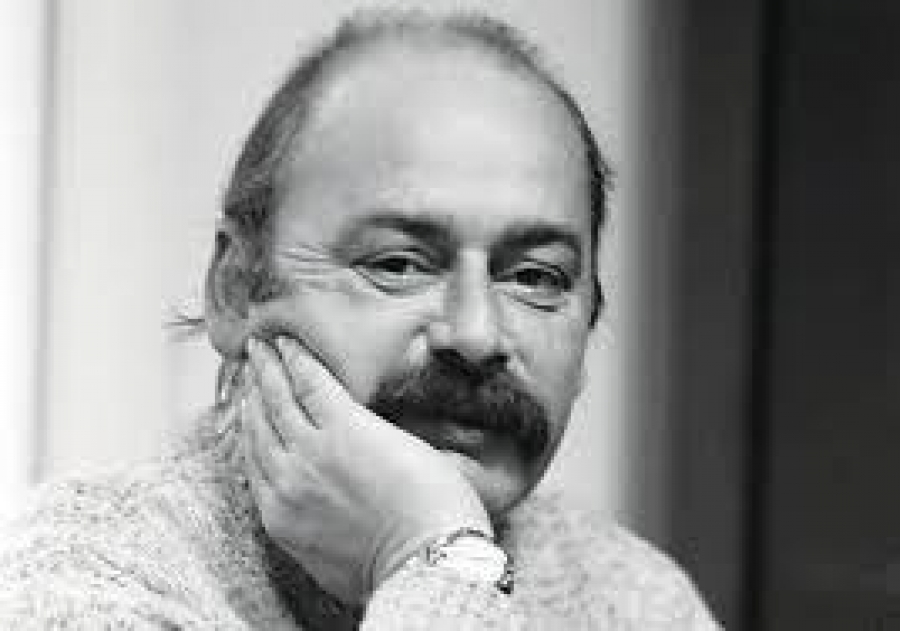

Teodor KEKO

Teodor KEKO

IN THE DARK

It kept on raining outside, a fine drizzle, cold and never-ending, so typical of Tirana in December. The electricity had been off in the apartment for some time. We continued to huddle in bed, silent and naked under the warm covers, listening to the patter of the rain against the windowpane. It was so frigid out of bed that you had to think twice before setting out on the long, five-metre journey to the bathroom. You'd piss a stalactite instead of urine.

Anna was not in good shape. Although she was the one who had called me and asked me to wait for her, and she was the one who had come here, who had disrobed and crawled into my bed as usual, she was not well. I pondered on this for quite a while, worrying whether I was perhaps the cause of her depression. She was still very young and far too beautiful to be depressed. But I never really found out why. From our first encounter at the jubilee concert, where very few people attended and where the singer was better at reciting the text of her song, written on the board, than she was at singing it, I had gotten along with Anna better than with anyone else. She had been a windfall for me from the start, a gift of God, a girl who, with so many admirers to choose from, had focussed her erotic attentions on me, a rusting thirty-five-year-old loser, abandoned by everyone else, who had set up house in the drinking parlour and spent his nights with a glass to fight off the biting solitude.

The moment her slender being entered my life, I seemed to revive. She also awakened my desire to get back to sculpting. Now I would concentrate on her curves and not on the usual portraits and busts of fallen heroes who had poisoned my lust for art the moment I came to realize that the results of my work, my personal collection, were all standing around in the cemetery. Yes, it was there that my masterpieces were languishing, paid for with a few leftover coins. Most of the busts were of thugs and savages struck down in some ambush, a settling of accounts, under circumstances and with weapons which were more or less identical, such that you would think they had all been killed by the same person.

Out of the corner of my eye, I observed her graceful back with its slight inward curve towards her bottom, and considered doing a couple of sketches. The light was fading, however, and work was now impossible. In the twilight, the result would probably have been the back of a fifty-year-old cleaning lady. I would just have to wait until the electricity came on again.

"It's still raining," she said at last. "I wonder why there's no light."

I studied her now, as if I were preparing to do a portrait, and could distinguish the sorrow in her being, a sorrow mixed with boredom.

"It's probably not raining up in the mountains."

"Damn rain," she growled, "it never rains in the North where the dams are, but here in Tirana where it does no one any good and just causes flooding!"

"You know, there was a time when people got along without electricity, day and night," I replied, endeavouring to console her.

"I know," she complained, "but life back then was designed that way and no one relied on electricity to start with. They may not have had light, but they had wood furnaces, coal stoves, chandeliers and candles."

"You're just in a bad mood," I ventured gently.

"I'm always terrified when the power is off," she responded. "The darkness reminds me of my life and, for an Albanian, that only means bad. We never have anything to remember..."

I tried to comfort her, noting that even the devil is not as black as he's painted, but my words were to no avail. Calmly, as if she were talking about a dress she had just bought, she informed me that life was not worth living. She defined our existence as a realm of mediocrity and futility, and I could find no argument to convince her of the contrary.

In fact, I could not remember anything from my past except the beatings I had received from my father every time he found out I was playing hooky, the death of my mother, and a few stupid moves I had made when I was out bingeing. I did not think much about the past anyway because I never had the courage to come to terms with reality. I was not one of those decisive, revolutionary types. Her depression was beginning to gnaw at me, too. She was a goddess, all that tender skin and those curves clinging to my body, and yet I could not touch her. It would have been perverse, a crime, to try to make love to something deprived of a soul...

"You know how I think of myself?" she then asked. "I'm like something... like some dead object!"

I had the impression she was wiping a tear from one of her wide eyes.

"You should not have come," I declared. "Now you've got me depressed, too!"

"You need the light more than I do! That's my only consolation. I think I would otherwise kill myself."

You are right, I thought to myself. If you were anywhere else, who knows where you would have ended up by now, in some well-lit bar, with a flickering crystal glass of champagne in your hand, surrounded by waiters dressed to the hilt.

Suddenly there was a click and the lights came on. The whole apartment building was abuzz. She sighed:

"I guess God's been listening in."

She rose at once and began to put on her clothes.

"Come on, get dressed," she demanded, as I looked on in surprise. "Let's go and get something to eat in a good restaurant before the lights go out again! I think I'd like to have a drink tonight." I was stunned and got up without delay. But I knew that the next morning she would be moaning again, day after day until she got old and would then look back, remembering only the death of her parents and the day they had ripped up her miniskirt. God had made her a beauty, but her beauty would never help her.

(November 2000)

[Në terr, from the volume Hollësira fatale, s.l. 2001, p. 46-48. Translated from the Albanian by Robert Elsie]